I wrote a statement that takes almost an hour to run so I am asking help so I can get to do this faster. So here we go:

I am making an inner join of two tables :

I have many time intervals represented by intervals and i want to get measure datas from measures only within those intervals.

intervals: has two columns, one is the starting time, the other the ending time of the interval (number of rows = 1295)

measures: has two columns, one with the measure, the other with the time the measure has been made (number of rows = one million)

The result I want to get is a table with in the first column the measure, then the time the measure has been done, the begin/end time of the considered interval (it would be repeated for row with a time within the considered range)

Here is my code:

select measures.measure as measure, measures.time as time, intervals.entry_time as entry_time, intervals.exit_time as exit_time

from

intervals

inner join

measures

on intervals.entry_time<=measures.time and measures.time <=intervals.exit_time

order by time asc

Thanks

This is quite a common problem.

Plain B-Tree indexes are not good for the queries like this:

SELECT measures.measure as measure,

measures.time as time,

intervals.entry_time as entry_time,

intervals.exit_time as exit_time

FROM intervals

JOIN measures

ON measures.time BETWEEN intervals.entry_time AND intervals.exit_time

ORDER BY

time ASC

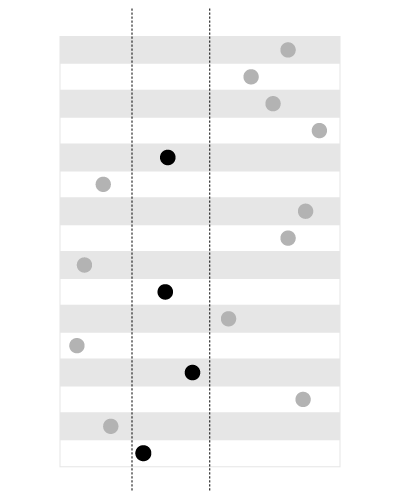

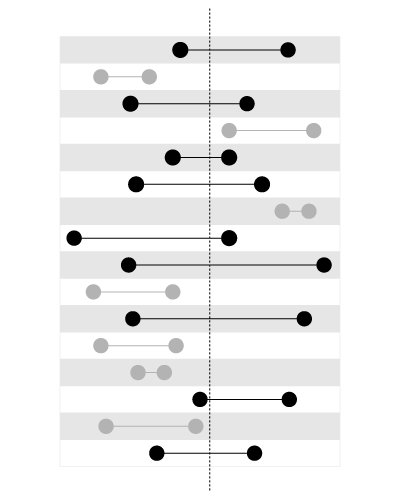

An index is good for searching the values within the given bounds, like this:

, but not for searching the bounds containing the given value, like this:

This article in my blog explains the problem in more detail:

(the nested sets model deals with the similar type of predicate).

You can make the index on time, this way the intervals will be leading in the join, the ranged time will be used inside the nested loops. This will require sorting on time.

You can create a spatial index on intervals (available in MySQL using MyISAM storage) that would include start and end in one geometry column. This way, measures can lead in the join and no sorting will be needed.

The spatial indexes, however, are more slow, so this will only be efficient if you have few measures but many intervals.

Since you have few intervals but many measures, just make sure you have an index on measures.time:

CREATE INDEX ix_measures_time ON measures (time)

Update:

Here's a sample script to test:

BEGIN

DBMS_RANDOM.seed(20091223);

END;

/

CREATE TABLE intervals (

entry_time NOT NULL,

exit_time NOT NULL

)

AS

SELECT TO_DATE('23.12.2009', 'dd.mm.yyyy') - level,

TO_DATE('23.12.2009', 'dd.mm.yyyy') - level + DBMS_RANDOM.value

FROM dual

CONNECT BY

level <= 1500

/

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX ux_intervals_entry ON intervals (entry_time)

/

CREATE TABLE measures (

time NOT NULL,

measure NOT NULL

)

AS

SELECT TO_DATE('23.12.2009', 'dd.mm.yyyy') - level / 720,

CAST(DBMS_RANDOM.value * 10000 AS NUMBER(18, 2))

FROM dual

CONNECT BY

level <= 1080000

/

ALTER TABLE measures ADD CONSTRAINT pk_measures_time PRIMARY KEY (time)

/

CREATE INDEX ix_measures_time_measure ON measures (time, measure)

/

This query:

SELECT SUM(measure), AVG(time - TO_DATE('23.12.2009', 'dd.mm.yyyy'))

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT /*+ ORDERED USE_NL(intervals measures) */

*

FROM intervals

JOIN measures

ON measures.time BETWEEN intervals.entry_time AND intervals.exit_time

ORDER BY

time

)

WHERE rownum <= 500000

)

uses NESTED LOOPS and returns in 1.7 seconds.

This query:

SELECT SUM(measure), AVG(time - TO_DATE('23.12.2009', 'dd.mm.yyyy'))

FROM (

SELECT *

FROM (

SELECT /*+ ORDERED USE_MERGE(intervals measures) */

*

FROM intervals

JOIN measures

ON measures.time BETWEEN intervals.entry_time AND intervals.exit_time

ORDER BY

time

)

WHERE rownum <= 500000

)

uses MERGE JOIN and I had to stop it after 5 minutes.

Update 2:

You will most probably need to force the engine to use the correct table order in the join using a hint like this:

SELECT /*+ LEADING (intervals) USE_NL(intervals, measures) */

measures.measure as measure,

measures.time as time,

intervals.entry_time as entry_time,

intervals.exit_time as exit_time

FROM intervals

JOIN measures

ON measures.time BETWEEN intervals.entry_time AND intervals.exit_time

ORDER BY

time ASC

The Oracle's optimizer is not smart enough to see that the intervals do not intersect. That's why it will most probably use measures as a leading table (which would be a wise decision should the intervals intersect).

Update 3:

WITH splits AS

(

SELECT /*+ MATERIALIZE */

entry_range, exit_range,

exit_range - entry_range + 1 AS range_span,

entry_time, exit_time

FROM (

SELECT TRUNC((entry_time - TO_DATE(1, 'J')) * 2) AS entry_range,

TRUNC((exit_time - TO_DATE(1, 'J')) * 2) AS exit_range,

entry_time,

exit_time

FROM intervals

)

),

upper AS

(

SELECT /*+ MATERIALIZE */

MAX(range_span) AS max_range

FROM splits

),

ranges AS

(

SELECT /*+ MATERIALIZE */

level AS chunk

FROM upper

CONNECT BY

level <= max_range

),

tiles AS

(

SELECT /*+ MATERIALIZE USE_MERGE (r s) */

entry_range + chunk - 1 AS tile,

entry_time,

exit_time

FROM ranges r

JOIN splits s

ON chunk <= range_span

)

SELECT /*+ LEADING(t) USE_HASH(m t) */

SUM(LENGTH(stuffing))

FROM tiles t

JOIN measures m

ON TRUNC((m.time - TO_DATE(1, 'J')) * 2) = tile

AND m.time BETWEEN t.entry_time AND t.exit_time

This query splits the time axis into the ranges and uses a HASH JOIN to join the measures and timestamps on the range values, with fine filtering later.

See this article in my blog for more detailed explanations on how it works:

To summarise: your query is running against the full set of MEASURES. It matches the time of each MEASURES record to an INTERVALS record. If the window of times spanned by INTERVALS is roughly similar to the window spanned by MEASURES then your query is also running against the full set of INTERVALS, otherwise it is running against a subset.

Why that matter is because it reduces your scope for tuning, as a full table scan is the likely to be the fastest way of getting all the rows. So, unless your real MEASURES or INTERVALS tables have a lot more columns than you give us, it is unlikely that any indexes will give much advantage.

The possible strategies are:

I'm not going to present test cases for all the permutations, because the results are pretty much as we would expect.

Here is the test data. As you can see I'm using slightly larger data sets. The INTERVALS window is bigger than the MEASURES windows but not by much. The intervals are 10000 seconds wide, and the measures are taken every 15 seconds.

SQL> select min(entry_time), max(exit_time), count(*) from intervals;

MIN(ENTRY MAX(EXIT_ COUNT(*)

--------- --------- ----------

01-JAN-09 20-AUG-09 2001

SQL> select min(ts), max(ts), count(*) from measures;

MIN(TS) MAX(TS) COUNT(*)

--------- --------- ----------

02-JAN-09 17-JUN-09 1200001

SQL>

NB In my test data I have presumed that INTERVAL records do not overlap. This has an important corrolary: a MEASURES record joins to only one INTERVAL.

Benchmark

Here is the benchmark with no indexes.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'MEASURES', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'INTERVALS', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> set timing on

SQL>

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:37.03

SQL>

MEASURES tests

Now let's build a unique index on INTERVALS (ENTRY_TIME, EXIT_TIME) and try out the various indexing strategies for MEASURES. First up, an index MEASURES TIME column only.

SQL> create index meas_idx on measures (ts)

2 /

Index created.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'MEASURES', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL>

SQL> set autotrace traceonly exp

SQL>

SQL> set timing on

SQL>

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:20.21

SQL>

Now, let us index MEASURES.TIME and MEASURE columns

SQL> drop index meas_idx

2 /

Index dropped.

SQL> create index meas_idx on measures (ts, measure)

2 /

Index created.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'MEASURES', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:28.54

SQL>

Now with no index on MEASURES (but still an index on INTERVALS)

SQL> drop index meas_idx

2 /

Index dropped.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'MEASURES', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:24.81

SQL>

So what difference does parallel query make ?

SQL> select /*+ parallel (4) */

2 m.measure

3 , m.ts as "TIME"

4 , i.entry_time

5 , i.exit_time

6 from

7 intervals i

8 inner join

9 measures m

10 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

11 order by m.ts asc

12 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:02:33.82

SQL>

MEASURES Conclusion

Not much difference in the elapsed time for the different indexes. I was slightly surprised that building an index on MEASURES (TS, MEASURE) resulted in a full table scan and a somewhat slower execution time. On the other hand, it is no surprise that running in parallel query is much faster. So if you have Enterprise Edition and you have the CPUs to spare, using PQ will definitely reduce the elapsed time, although it won't change the resource costs much (and actually does a lot more sorting).

INTERVALS tests

So what difference might the various indexes on INTERVALS make? In the following tests we will retain an index on MEASURES (TS). First of all we will drop the primary key on both INTERVALS columns and replace it with a constraint on INTERVALS (ENTRY_TIME) only.

SQL> alter table intervals drop constraint ivl_pk drop index

2 /

Table altered.

SQL> alter table intervals add constraint ivl_pk primary key (entry_time) using index

2 /

Table altered.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'INTERVALS', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:38.39

SQL>

Lastly with no index on INTERVALS at all

SQL> alter table intervals drop constraint ivl_pk drop index

2 /

Table altered.

SQL> exec dbms_stats.gather_table_stats(user, 'INTERVALS', cascade=>true)

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> select m.measure

2 , m.ts as "TIME"

3 , i.entry_time

4 , i.exit_time

5 from

6 intervals i

7 inner join

8 measures m

9 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

10 order by m.ts asc

11 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:05:29.15

SQL>

INTERVALS conclusion

The index on INTERVALS makes a slight difference. That is, indexing (ENTRY_TIME, EXIT_TIME) results in a faster execution. This is because it permist a fast full index scan rather than a full table scan. This would be more significant if the time window delineated by INTERVALS was considerably wider than that of MEASURES.

Overall Conclusions

Because we are doing full table queries none of the indexes substantially changed the execution time. So if you have Enterprise Edition and multiple CPUs Parallel Query will give you the best results. Otherwise the most best indexes would be INTERVALS(ENTRY_TIME, EXIT_TIME) and MEASURES(TS) . The Nested Loops solution is definitely faster than Parallel Query - see Edit 4 below.

If you were running against a subset of MEASURES (say a week's worth) then the presence of indexes would have a bigger impact, It is likely that the two I recommended in the previous paragraph would remain the most effective,

Last observation: I ran this on a bog standard dual core laptop with an SGA of just 512M. Yet all of my queries took less than six minutes. If your query really takes an hour then your database has some serious problems. Although this long running time could be an artefact of overlapping INTERVALS, which could result in a cartesian product.

**Edit **

Originally I included the output from

SQL> set autotrace traceonly stat exp

But alas SO severely truncated my post. So I have rewritten it but without execution or stats. Those who wish to validate my findings will have to run the queries themselevs.

Edit 4 (previous edit's removed for reasons of space)

At the third attempt I have been able to reproduce teh performance improvement for Quassnoi's solution.

SQL> set autotrace traceonly stat exp

SQL>

SQL> set timing on

SQL>

SQL> select

2 /*+ LEADING (i) USE_NL(i, m) */

3 m.measure

4 , m.ts as "TIME"

5 , i.entry_time

6 , i.exit_time

7 from

8 intervals i

9 inner join

10 measures m

11 on ( m.ts between i.entry_time and i.exit_time )

12 order by m.ts asc

13 /

1200001 rows selected.

Elapsed: 00:00:18.39

Execution Plan

----------------------------------------------------------

Plan hash value: 974071908

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Id | Operation | Name | Rows | Bytes |TempSpc| Cost (%CPU)| Time |

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| 0 | SELECT STATEMENT | | 6003K| 257M| | 973K (1)| 03:14:46 |

| 1 | SORT ORDER BY | | 6003K| 257M| 646M| 973K (1)| 03:14:46 |

| 2 | NESTED LOOPS | | | | | | |

| 3 | NESTED LOOPS | | 6003K| 257M| | 905K (1)| 03:01:06 |

| 4 | TABLE ACCESS FULL | INTERVALS | 2001 | 32016 | | 2739 (1)| 00:00:33 |

|* 5 | INDEX RANGE SCAN | MEAS_IDX | 60000 | | | 161 (1)| 00:00:02 |

| 6 | TABLE ACCESS BY INDEX ROWID| MEASURES | 3000 | 87000 | | 451 (1)| 00:00:06 |

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Predicate Information (identified by operation id):

---------------------------------------------------

5 - access("M"."TS">="I"."ENTRY_TIME" AND "M"."TS"<="I"."EXIT_TIME")

Statistics

----------------------------------------------------------

66 recursive calls

2 db block gets

21743 consistent gets

18175 physical reads

0 redo size

52171689 bytes sent via SQL*Net to client

880416 bytes received via SQL*Net from client

80002 SQL*Net roundtrips to/from client

0 sorts (memory)

1 sorts (disk)

1200001 rows processed

SQL>

So Nested Loops are definitely the way to go.

Useful lessons from the exercise

If you love us? You can donate to us via Paypal or buy me a coffee so we can maintain and grow! Thank you!

Donate Us With