Rebasing can be dangerous! Rewriting history of shared branches is prone to team work breakage. This can be mitigated by doing the rebase/squash on a copy of the feature branch, but rebase carries the implication that competence and carefulness must be employed.

With the cherry-pick command, Git lets you incorporate selected individual commits from any branch into your current Git HEAD branch. When performing a git merge or git rebase , all the commits from a branch are combined. The cherry-pick command allows you to select individual commits for integration.

It is best practice to always rebase your local commits when you pull before pushing them. As nobody knows your commits yet, nobody will be confused when they are rebased but the additional commit of a merge would be unnecessarily confusing.

Use rebase whenever you want to add changes of a base branch back to a branched out branch. Typically, you do this in feature branches whenever there's a change in the main branch.

Since the time git cherry-pick learned to be able to apply multiple commits, the distinction indeed became somewhat moot, but this is something to be called convergent evolution ;-)

The true distinction lies in original intent to create both tools:

git rebase's task is to forward-port a series of changes a developer has in their private repository, created against version X of some upstream branch, to version Y of that same branch (Y > X). This effectively changes the base of that series of commits, hence "rebasing".

(It also allows the developer to transplant a series of commits onto any arbitrary commit, but this is of less obvious use.)

git cherry-pick is for bringing an interesting commit from one line of development to another. A classic example is backporting a security fix made on an unstable development branch to a stable (maintenance) branch, where a merge makes no sense, as it would bring a whole lot of unwanted changes.

Since its first appearance, git cherry-pick has been able to pick several commits at once, one-by-one.

Hence, possibly the most striking difference between these two commands is how they treat the branch they work on: git cherry-pick usually brings a commit from somewhere else and applies it on top of your current branch, recording a new commit, while git rebase takes your current branch and rewrites a series of its own tip commits in one way or another. Yes, this is a heavily dumbed down description of what git rebase can do, but it's intentional, to try to make the general idea sink in.

Update to further explain an example of using git rebase being discussed.

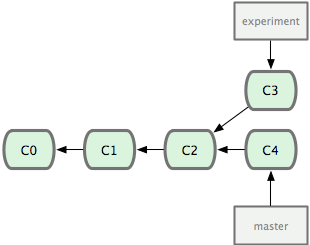

Given this situation,

The Book states:

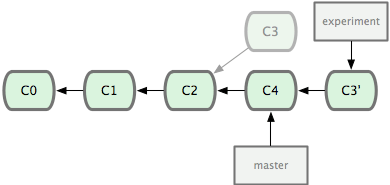

However, there is another way: you can take the patch of the change that was introduced in C3 and reapply it on top of C4. In Git, this is called rebasing. With the rebase command, you can take all the changes that were committed on one branch and apply them onto another one.

In this example, you’d run the following:

$ git checkout experiment $ git rebase master First, rewinding head to replay your work on top of it... Applying: added staged command

"The catch" here is that in this example, the "experiment" branch (the subject for rebasing) was originally forked off the "master" branch, and hence it shares commits C0 through C2 with it — effectively, "experiment" is "master" up to, and including, C2 plus commit C3 on top of it. (This is the simplest possible case; of course, "experiment" could contain several dozens of commits on top of its original base.)

Now git rebase is told to rebase "experiment" onto the current tip of "master", and git rebase goes like this:

git merge-base to see what's the last commit shared by both "experiment" and "master" (what's the point of diversion, in other words). This is C2.git apply) in order. In our toy example it's just one commit, C3. Let's say its application will produce a commit C3'.Now back to your question. As you can see, here technically git rebase indeed transplants a series of commits from "experiment" to the tip of "master", so you can rightfully tell there indeed is "another branch" in the process. But the gist is that the tip commit from "experiment" ended up being the new tip commit in "experiment", it just changed its base:

Again, technically you can tell that git rebase here incorporated certain commits from "master", and this is absolutely correct.

With cherry-pick, the original commits/branch sticks around and new commits are created. With rebase, the whole branch is moved with the branch pointing to the replayed commits.

Let say you started with:

A---B---C topic

/

D---E---F---G master

Rebase:

$ git rebase master topic

You get:

A'--B'--C' topic

/

D---E---F---G master

Cherry-pick:

$ git checkout master -b topic_new

$ git cherry-pick A^..C

You get:

A---B---C topic

/

D---E---F---G master

\

A'--B'--C' topic_new

for more info about git this book has most of it (http://git-scm.com/book)

Cherry-picking works for individual commits.

When you do rebasing it applies all commits in the history to the HEAD of the branch that are missing there.

A short answer:

Answers given above are good, I just wanted to give an example in an attempt to demonstrate their interrelation.

It is not recommended to replace "git rebase" with this sequence of actions, it's just "a proof of concept" which, I hope, helps to understand how things work.

Given the following toy repository:

$ git log --graph --decorate --all --oneline

* 558be99 (test_branch_1) Test commit #7

* 21883bb Test commit #6

| * 7254931 (HEAD -> master) Test commit #5

| * 79fd6cb Test commit #4

| * 48c9b78 Test commit #3

| * da8a50f Test commit #2

|/

* f2fa606 Test commit #1

Say, we have some very important changes (commits #2 through #5) in master which we want to include into our test_branch_1. Usually we just switch to a branch and do "git rebase master". But as we are pretending we are only equipped with "git cherry-pick", we do:

$ git checkout 7254931 # Switch to master (7254931 <-- master <-- HEAD)

$ git cherry-pick 21883bb^..558be99 # Apply a range of commits (first commit is included, hence "^")

After all these operations our commit graph will look like this:

* dd0d3b4 (HEAD) Test commit #7

* 8ccc132 Test commit #6

* 7254931 (master) Test commit #5

* 79fd6cb Test commit #4

* 48c9b78 Test commit #3

* da8a50f Test commit #2

| * 558be99 (test_branch_1) Test commit #7

| * 21883bb Test commit #6

|/

* f2fa606 Test commit #1

As we can see, commits #6 and #7 were applied against 7254931 (a tip commit of master). HEAD was moved and points a commit which is, essentially, a tip of a rebased branch. Now all we need to do is delete an old branch pointer and create a new one:

$ git branch -D test_branch_1

$ git checkout -b test_branch_1 dd0d3b4

test_branch_1 is now rooted from the latest master position. Done!

They're both commands for rewriting the commits of one branch on top of another: the difference is in which branch - "yours" (the currently checked out HEAD) or "theirs" (the branch passed as an argument to the command) - is the base for this rewrite.

git rebase takes a starting commit and replays your commits as coming after theirs (the starting commit).

git cherry-pick takes a set of commits and replays their commits as coming after yours (your HEAD).

In other words, the two commands are, in their core behavior (ignoring their divergent performance characteristics, calling conventions, and enhancement options), symmetrical: checking out branch bar and running git rebase foo sets the bar branch to the same history as checking out branch foo and running git cherry-pick ..bar would set foo to (the changes from foo, followed by the changes from bar).

Naming-wise, the difference between the two commands can be remembered in that each one describes what it does to the current branch: rebase makes the other head the new base for your changes, whereas cherry-pick picks changes from the other branch and puts them on top of your HEAD (like cherries on top of a sundae).

If you love us? You can donate to us via Paypal or buy me a coffee so we can maintain and grow! Thank you!

Donate Us With