The ledger balance shows the total amount of money in your account, but the total amount of funds may not be ready to use. For instance, checks or deposits may still need to be cleared by your bank. The available balance is the ledger balance minus any transactions made throughout the day.

Your account balance is the total in your account. If you see “OD” (meaning Overdraft) in front of the amount, this is the amount you owe. Available balance represents the funds you are able to withdraw, transfer and use.

A current balance is the amount of cash presently sitting in a checking or savings account at any given time. However, the available balance is the current balance minus any pending transactions that haven't been fully processed yet.

Your available balance is the total amount of money in your account that you can use for purchases and withdrawals, as it excludes pending transactions and check holds from your account balance. However, the available balance will not show checks that haven't been cashed or deposits which haven't posted.

Preface

There is an objective truth: Audit requirements. Additionally, when dealing with public funds, there is Legislature that must be complied with.

You don't have to implement the full accounting requirement, you can implement just the parts that you need.

Conversely, it would be ill-advised to implement something other than the standard accounting requirement (the parts thereof) because that guarantees that when the number of bugs or the load exceeds some threshold, or the system expands,you will have to re-implement. A cost that can, and therefore should, be avoided.

It also needs to be stated: do not hire an unqualified, un-accredited "auditor". There will be consequences, the same as if you hired an unqualified developer. It might be worse, if the Tax Office fines you.

The Standard Accounting method in not-so-primitive countries is this. The "best practice", if you will, in others.

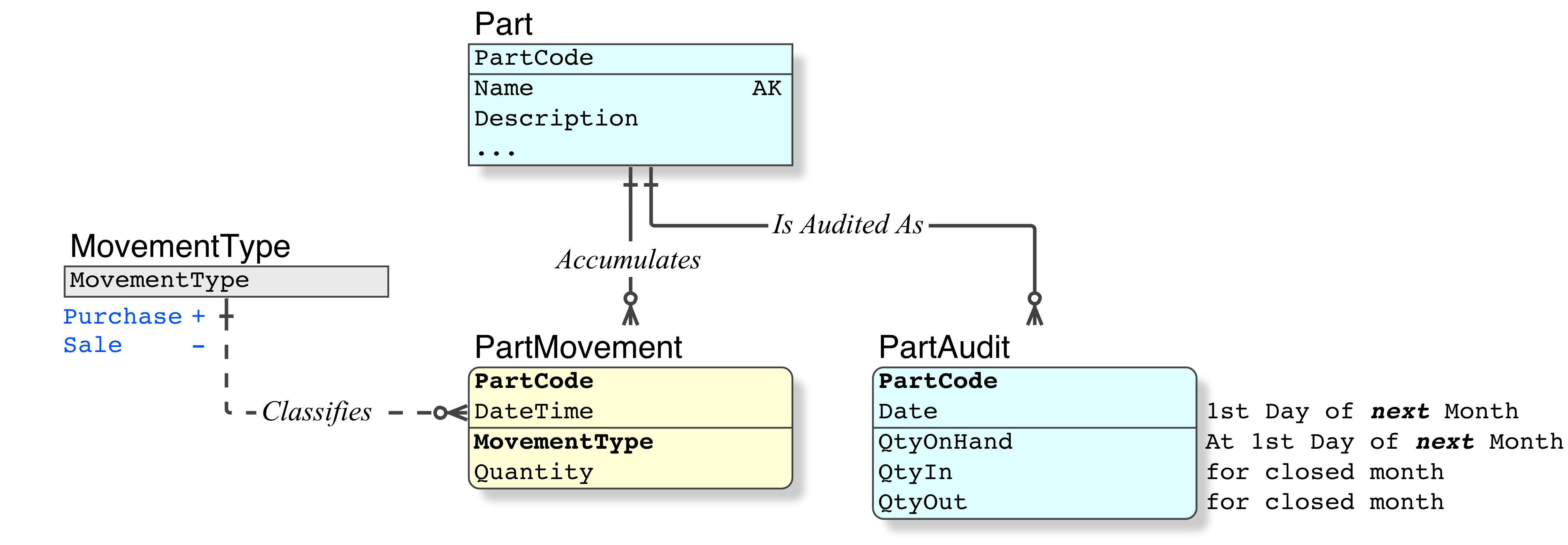

This method applies to any system that has similar operations; needs; historic monthly figures vs current-month requirements, such as Inventory Control, etc.

First, the considerations.

Never duplicate data.

If the Current Balance can be derived (and here it is simple), do not duplicate it with a summary column. Such a column is a duplication of data. It breaks Normalisation rules. Further, it creates an Update Anomaly, which otherwise does not exist.

If you do use a summary column, whenever the Transactions are updated (as in changed, not as in when a new Transaction is inserted), the summary column value becomes obsolete, so it must be updated all the time anyway. That is the consequence of the Update Anomaly. Which eliminates the value of having it.

External publication.

Separate point. If the balance is published, as in a monthly Bank Statement, such documents usually have legal restrictions and implications, thus that published Current Balance value must not change after publication.

Any change, after the publication date, in the database, of a figure that is published externally, is evidence of dishonest conduct, fraud, etc.

You wouldn't want your bank, in Apr 2015, to change your Current Balance that they published in their Bank Statement to you of Dec 2014.

That figure has to be viewed as an Audit figure, published and unchangeable.

To correct an error that was made in the past, that is being corrected in the present, the correction or adjustment that is necessary, is made as new Transactions in the current month (even though it applies to some previous month or duration).

This is because that applicable-to month is closed; Audited; and published, because one cannot change history after it has happened and it has been recorded. The only effective month is the current one.

For interest-bearing systems, etc, in not-so-primitive countries, when an error is found, and it has an historic effect (eg. you find out in Apr 2015 that the interest calculated on a security has been incorrect, since Dec 2014), the value of the corrected interest payment/deduction is calculated today, for the number of days that were in error, and the sum is inserted as a Transaction in the current month. Again, the only effective month is the current one.

And of course, the interest rate for the security has to be corrected as well, so that that error does not repeat.

If you find an error in your bank's calculation of the interest on your Savings (interest-bearing) Account, and you have it corrected, you get a single deposit, that constitutes the whole adjustment value, in the current month. That is a Transaction in the current month.

The bank does not: change history; apply interest for each of the historic months; recall the historic Bank Statements; re-publish the historic Bank Statements. No. Except maybe in third world countries.

The same principles apply to Inventory control systems. It maintains sanity.

All real accounting systems (ie. those that are accredited by the Audit Authority in the applicable country, as opposed to the Mickey Mouse "packages" that abound) use a Double Entry system for Transactions, precisely because it prevents a raft of errors, the most important of which is, funds do not get "lost". That requires a General Ledger and Double-Entry Accounting.

This Answer services the Question that is asked, which is not Double-Entry Accounting.

For a full treatment of that subject (detailed data model; examples of accounting Transactions; rows affected; and SQL code examples), refer to this Q&A:

Relational Data Model for Double-Entry Accounting.

The major issues that affect performance are outside the scope of this question, they are in the area of whether you implement a genuine Relational Database or not (eg. a 1960's Record Filing System, which is characterised by Record IDs, deployed in an SQL database container for convenience).

The use of genuine Relational Keys, etc will maintain high performance, regardless of the population of the tables.

Conversely, an RFS will perform badly, they simply cannot perform. "Scale" when used in the context of an RFS, is a fraudulent term: it hides the cause and seeks to address everything but the cause. Most important, such systems have none of the Relational Integrity; the Relational Power; or the Relational Speed, of a Relational system.

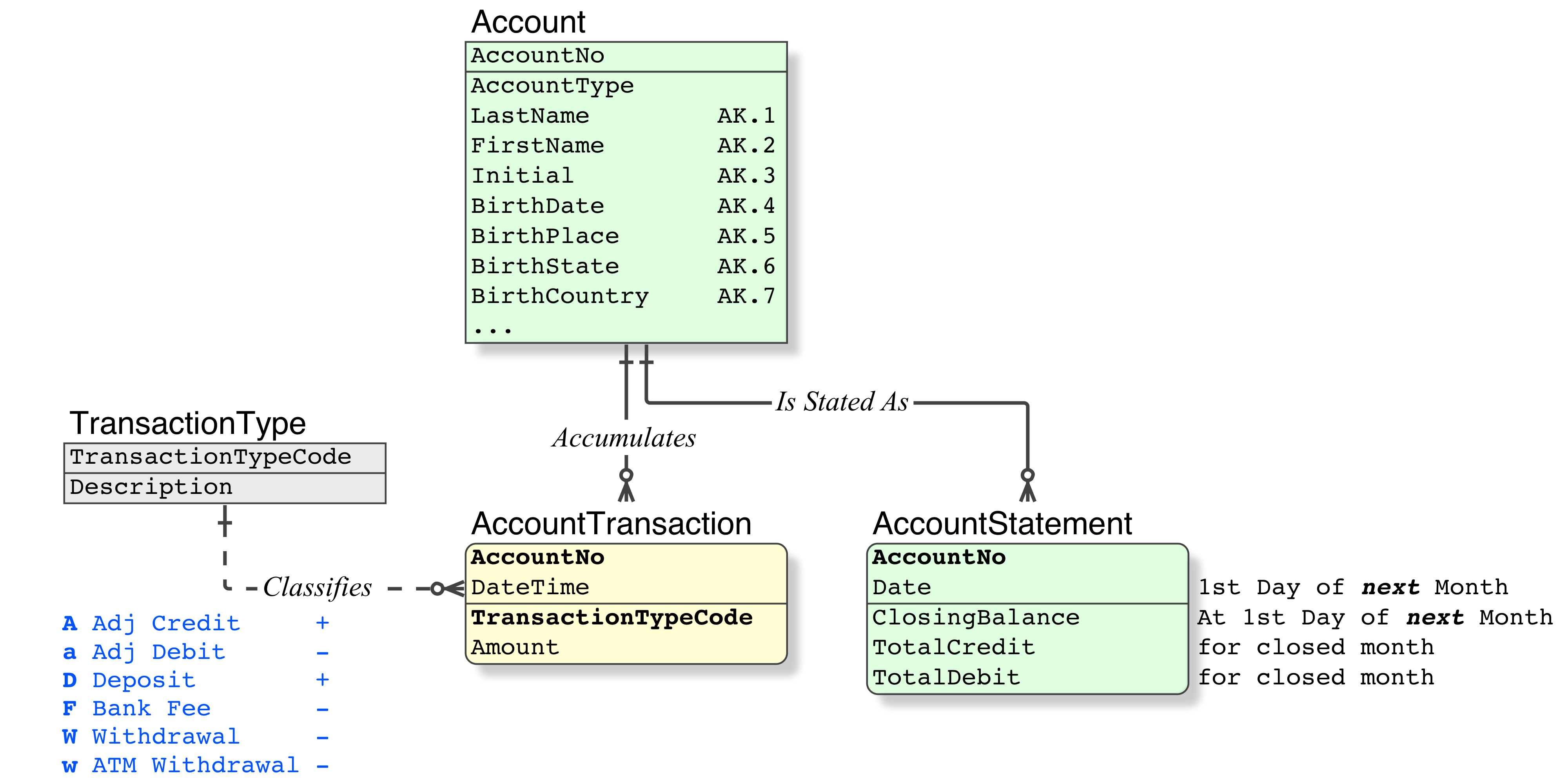

All my data models are rendered in IDEF1X, the Standard for modelling Relational databases since 1993.

My IDEF1X Introduction is essential reading for those who are new to the Relational Model, or its modelling method. Note that IDEF1X models are rich in detail and precision, showing all required details, whereas home-grown models have far less than that. Which means, the notation has to be understood.

For each Account, there will be a ClosingBalance, in a AccountStatement table (one row per AccountNo per month), along with Statement Date (usually the first day of the month) and other Statement details.

This is not a duplicate because it is demanded for Audit and sanity purposes.

For Inventory, it is a QtyOnHand column, in the PartAudit table (one row per PartCode per month)

It has an additional value, in that it constrains the scope of the Transaction rows required to be queried to the current month

Again, if your table is Relational, the Primary Key for AccountTransaction will be (AccountNo, Transaction DateTime) which will retrieve the Transactions at millisecond speeds.

Whereas for a Record Filing System, the "primary key" will be TransactionID, and you will be retrieving the current month by Transaction Date, which may or may not be indexed correctly, and the rows required will be spread across the file. In any case at far less than ClusteredIndex speeds, and due to the spread, it will incur a tablescan.

The AccountTransaction table remains simple (the real world notion of a bank account Transaction is simple). It has a single positive Amount column.

For each Account, the CurrentBalance is:

the AccountStatement.ClosingBalance of the previous month, dated the first of the next month for convenience

(for inventory, the PartAudit.QtyOnHand)

plus the SUM of the AccountTransaction.Amounts in the current month, where the TransactionType indicates a deposit

(for inventory, the PartMovement.Quantity)

minus the SUM of the AccountTransaction.Amounts in the current month, where the `MovementType indicates a withdrawal.

In this Method, the AccountTransactions in the current month, only, are in a state of flux, thus they must be derived. All previous months are published and closed, thus the Audit figure must be used.

The older rows in the AccountTransaction table can be purged. Older than ten years for public money, five years otherwise, one year for hobby club systems.

Of course, it is essential that any code relating to accounting systems uses genuine OLTP Standards and genuine SQL ACID Transactions.

This design incorporates all scope-level performance considerations (if this is not obvious, please ask for expansion). Scaling inside the database is a non-issue, any scaling issues that remain are honestly outside database.

These items need to be stated only because incorrect advice has been provided in many SO Answers (and up-voted by the masses, democratically, of course), and the internet is chock-full of incorrect advice (amateurs love to publish their subjective "truths"):

Evidently, some people do not understand that I have given a Method in technical terms, to operate against a clear data model. As such, it is not pseudo-code for a specific application in a specific country. The Method is for capable developers, it is not detailed enough for those who need to be lead by the hand.

They also do not understand that the cut-off period of a month is an example: if your cut-off for Tax Office purposes is quarterly, then by all means, use a quarterly cut-off; if the only legal requirement you have is annual, use annual.

Even if your cut-off is quarterly for external or compliance purposes, the company may well choose a monthly cut-off, for internal Audit and sanity purposes (ie. to keep the length of the period of the state of flux to a minimum).

Eg. in Australia, the Tax Office cut-off for businesses is quarterly, but larger companies cut-off their inventory control monthly (this saves having to chase errors over a long period).

Eg. banks have legal compliance requirements monthly, therefore they perform an internal Audit on the figures, and close the books, monthly.

In primitive countries and rogue states, banks keep their state-of-flux period at the maximum, for obvious nefarious purposes. Some of them only make their compliance reports annually. That is one reason why the banks in Australia do not fail.

In the AccountTransaction table, do not use negative/positive in the Amount column. Money always has a positive value, there is no such thing as negative twenty dollars (or that you owe me minus fifty dollars), and then working out that the double negatives mean something else.

The movement direction, or what you are going to do with the funds, is a separate and discrete fact (to the AccountTransaction.Amount). Which requires a separate column (two facts in one datum breaks Normalisation rules, with the consequence that it introduces complexity into the code).

Implement a TransactionType reference table, the Primary Key of which is (D, W ) for Deposit/Withdrawal as your starting point. As the system grows, simply add ( A, a, F, w ) for Adjustment Credit; Adjustment Debit; Bank Fee; ATM_Withdrawal; etc.

No code changes required.

In some primitive countries, litigation requirements state that in any report that lists Transactions, a running total must be shown on every line. (Note, this is not an Audit requirement because those are superior [(refer Method above) to the court requirement; Auditors are somewhat less stupid than lawyers; etc.)

Obviously, I would not argue with a court requirement. The problem is that primitive coders translate that into: oh, oh, we must implement a AccountTransaction.CurrentBalance column. They fail to understand that:

the requirement to print a column on a report is not a dictate to store a value in the database

a running total of any kind is a derived value, and it is easily coded (post a question if it isn't easy for you). Just implement the required code in the report.

implementing the running total eg. AccountTransaction.CurrentBalance as a column causes horrendous problems:

introduces a duplicated column, because it is derivable. Breaks Normalisation. Introduces an Update Anomaly.

the Update Anomaly: whenever a Transaction is inserted historically, or a AccountTransaction.Amount is changed, all the AccountTransaction.CurrentBalances from that date to the present have to be re-computed and updated.

in the above case, the report that was filed for court use, is now obsolete (every report of online data is obsolete the moment it is printed). Ie. print; review; change the Transaction; re-print; re-review, until you are happy. It is meaningless in any case.

which is why, in less-primitive countries, the courts do not accept any old printed paper, they accept only published figures, eg. Bank Statements, which are already subject to Audit requirements (refer the Method above), and which cannot be recalled or changed and re-printed.

Alex:

yes code would be nice to look at, thank you. Even maybe a sample "bucket shop" so people could see the starting schema once and forever, would make world much better.

For the data model above.

SELECT AccountNo,

ClosingDate = DATEADD( DD, -1 Date ), -- show last day of previous

ClosingBalance,

CurrentBalance = ClosingBalance + (

SELECT SUM( Amount )

FROM AccountTransaction

WHERE AccountNo = @AccountNo

AND TransactionTypeCode IN ( "A", "D" )

AND DateTime >= CONVERT( CHAR(6), GETDATE(), 2 ) + "01"

) - (

SELECT SUM( Amount )

FROM AccountTransaction

WHERE AccountNo = @AccountNo

AND TransactionTypeCode NOT IN ( "A", "D" )

AND DateTime >= CONVERT( CHAR(6), GETDATE(), 2 ) + "01"

)

FROM AccountStatement

WHERE AccountNo = @AccountNo

AND Date = CONVERT( CHAR(6), GETDATE(), 2 ) + "01"

By denormalising that transactions log I trade normal form for more convenient queries and less changes in views/materialised views when I add more tx types

God help me.

When you go against Standards, you place yourself in a third-world position, where things that are not supposed to break, that never break in first-world countries, break.

It is probably not a good idea to seek the right answer from an authority, and then argue against it, or argue for your sub-standard method.

Denormalising (here) causes an Update Anomaly, the duplicated column, that can be derived from TransactionTypeCode. You want ease of coding, but you are willing to code it in two places, rather than one. That is exactly the kind of code that is prone to errors.

A database that is fully Normalised according to Dr E F Codd's Relational Model provides for the easiest, the most logical, straight-forward code. (In my work, I contractually guarantee every report can be serviced by a single SELECT.)

ENUM is not SQL. (The freeware NONsql suites have no SQL compliance, but they do have extras which are not required in SQL.) If ever your app graduates to a commercial SQL platform, you will have to re-write all those ENUMs as ordinary LookUp tables. With a CHAR(1) or a INT as the PK. Then you will appreciate that it is actually a table with a PK.

An error has a value of zero (it also has negative consequences). A truth has a value of one. I would not trade a one for a zero. Therefore it is not a trade-off. It is just your development decision.

This is fairly subjective. The things I'd suggest taking into account are:

In terms of the merits of the two approaches proposed, summing the transaction values on-demand is likely to be the easier/quicker to implement approach.

However, it won't scale as well as maintaining the current account balance as a field in the database and updating it as you go. And it increases your overall transaction processing time somewhat, as each transaction needs to run a query to compute the current account balance before it can proceed. In practice those may be small concerns unless you have a very large number of accounts/transactions or expect to in the very near future.

The downside of the second approach is that it's probably going to take more development time/effort to set up initially, and may require that you give some thought to how you synchronize transactions within an account to ensure that each one sees and updates the balance accurately at all times.

So it mostly comes down to what the project's needs are, where development time is best spent at the moment, and whether it's worth future-proofing the solution now as opposed to implementing the second approach later on, when performance and scalability become real, rather than theoretical, problems.

If you love us? You can donate to us via Paypal or buy me a coffee so we can maintain and grow! Thank you!

Donate Us With